This is part 12 of a multi-part series on the book of Mark.

Today, we’re in Mark 12:13-17.

The Pharisees are desperate. Religiously pure people, their goal was to obey – and get all God’s people to obey – all 613 OT laws so that they could avoid another exile and get the yoke of Rome off their backs.

Meanwhile, the Herodians were a politically-motivated bunch, having gained considerably from Herod’s Judean rule sanctioned by Caesar. They were the quintessential opportunists of their day (even above the tax collectors), finding a way to win from Roman rule and ignoring the negative impacts to their own people.

One would assume, then, that the Pharisees and the Herodians would be bitter enemies. For them to collude would mean a much larger enemy must be present: enter Jesus.

The two “frenemy” groups went to trap Jesus with a question: is it lawful to pay taxes to Caesar or not? The logic was this: if Jesus says “yes,” then he is supporting Roman rule over God’s people, a deeply unpopular view. If he says “no,” then he is captured in his speech supporting insurrection against Rome. It’s a sure win for the Herodisees (get it: Herodians + Pharisees? Okay, I won’t say that again).

Yet the irony is thick: the Herodians ARE in bed with Rome, holding that deeply unpopular view with everyday Jews. They are trying to catch Jesus in something that they already hold to. No matter which way Jesus answers, he would be agreeing with either the Pharisees or the Herodians, but they both want him dead before he even answers. Their plot is sick and twisted.

Jesus knew their hypocrisy and asked them why they were testing him. He asked for a denarius and as usual – responded to their question with a question: “Whose likeness and inscription is this?” They answered, “Caesar’s” (12:16). Then the KO punch: “Render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s.” All they could do was marvel (12:17).

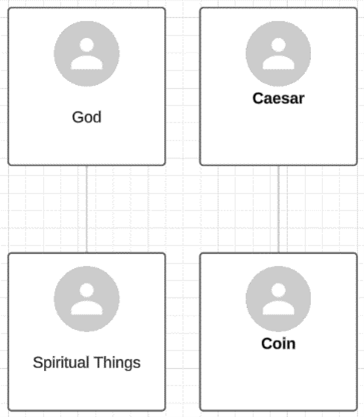

This was a more brilliant answer than we might see on the surface. Jesus simultaneously avoided answering the question directly while answering it in much stronger terms than they were even asking for. We often read a sacred/secular divide into this passage: we read Jesus as saying that we should give the coin to Caesar because the things of this world are his but we should give things of God to God. But is that really what Jesus was saying?

Jesus WAS NOT saying that the coin belonged to Caesar rather than to God – that God wasn’t powerful enough or didn’t care enough to own the denarius. Psalm 24:1 declares that the earth is the LORD’s and everything in it. Everything – even that little denarius.

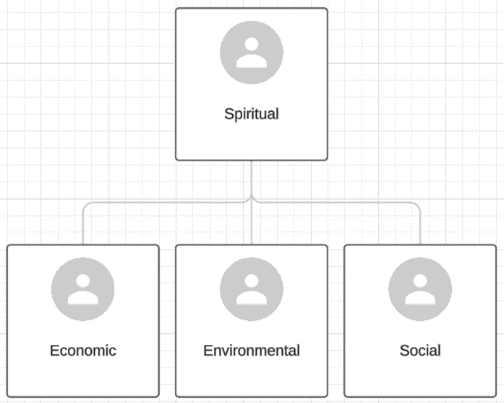

As westerners, we tend to break up everything into buckets or categories – even in BAM: economic, social, environmental, spiritual. But the borders between facets of life are at best fluid and at worst nonexistent. Nonetheless, we try to view the world through these artificial constraints such that we hear Jesus saying: this coin is for Caesar (economic), but worship is for God (spiritual).

Because we live in democracies (which I’m not claiming is bad), we tend not to see things very differently than we would if we lived in a kingdom: we owe our governments limited allegiance and a share of our own earnings as tax revenue. Yet, our governments don’t own our property – we do. The government owns this, we own that.

Jesus did not view the world the same way we do. He looked at life as a hierarchy, which is the proper view of life when living in a Kingdom. Jesus obeyed while setting aside the Roman system of taxes and property rights, acknowledging only that Caesar had power because it was given to him from above. In fact, Jesus would shortly thereafter say this in no uncertain terms to a Jewish mob and a Roman official, respectively: “Do you think that I cannot appeal to my Father, and he will at once send me more than twelve legions of angels?” (Matthew 26:53); “You would have no authority over me at all unless it had been given you from above. Therefore he who delivered me over to you has the greater sin” (John 19:11).

The person who seemed to understand best the system Jesus endorsed was the Roman centurion whose servant Jesus healed: “Lord, I am not worthy to have you come under my roof, but only say the word and my servant will be healed. For I too am a man under authority, with soldiers under me. And I say to one, “Go,” and he goes, and to another, ”Come,” and he comes, and to my servant, “Do this,” and he does it.” Jesus marveled at his understanding of the Kingdom.

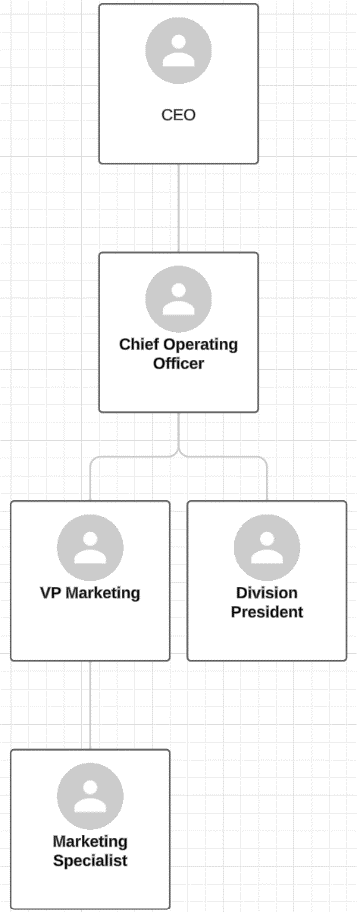

Instead of seeing things as horizontal buckets, we should view them as a vertical hierarchy like an organizational chart:

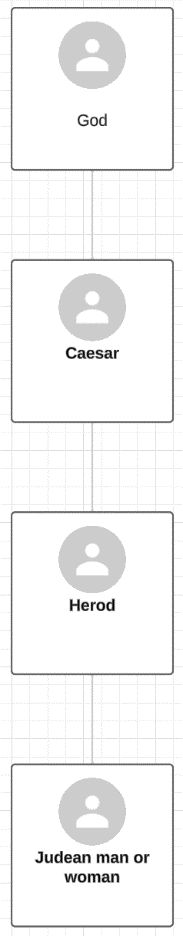

or:

Take in the argument carefully, because Paul comes from a different set of assumptions than we do: there is a hierarchy here. God is King over all of it and thus owns all of it. Yet in his wisdom he allows ownership down the hierarchy all the way to me. But may I never forget that what I own is under the authority of the King and thus, loosely speaking, I am a steward. Hence all the parables about stewards and how we are accountable to him in how we use the resources under our care.

It’s sort of like a child owning something. The parent still has the right to take it away when the child misbehaves, because anything that belongs to a child falls under the jurisdiction of the parents. Anything that is Caesar’s is ultimately God’s, but God employs Caesar to steward a particular portion of His empire for reasons that are beyond our ability to comprehend, though admittedly many of us would turn into Caesar if we had that sort of power…

Let’s take this even further. They looked at the coin and saw the likeness of Caesar, but when they looked at a man they should have seen the likeness of God. If the coin belonged most immediately to Caesar, Jesus belonged to God as one in his likeness. Yet, missing that critical point, they were content to take Jesus’ life because he threatened their rule, which ultimately also fell under the authority of the only wise King.

We look at the world like this:

But instead we should now see it like this:

All of this brings us back to Genesis. We were created to rule and reign, but always under the umbrella of God’s ultimate reign. Jesus came to restore that order, and his logic here supports that Caesar had a limited rule given to him by God and he has been given stewardship over the Roman Empire for which taxes are good and right to pay – but because his rule is not ultimate, he will answer for how he conducts it on That Day. So must we!

To learn more about B4T, read Business for Transformation by Patrick Lai.

- Blog Home

- /

- Uncategorized

- /

- MARK 12, PT 1...